- Home

- Christina Haag

Come to the Edge Page 3

Come to the Edge Read online

Page 3

…

I knew when I was young that I went to school in a castle, and I knew that this wasn’t normal, but the small evidences of ruin—a chipped column, a faded tapestry—gave intimacy to the splendor, so it seemed it really was someone’s house. The nuns would say God’s house. And perhaps they were right. But from those years and from that place, I had the sense that brokenness meant approach and that beauty was something mixed of shadow and decay. That it was made, in part, from the pieces of the past and the things that are left behind.

I wonder if I was born nostalgic. It’s possible it’s in the blood, a predetermined trait like green eyes or flat feet. And it may well be that some ancestor on a sea crossing was filled with longing for what was gone—out of grief or pleasure, or simply to make the time pass on the ship.

I remember the first time I felt that kind of longing. I was standing in the hallway outside the first-grade classroom, eyes smarting and nose beginning to run. I’d been sent there by Sister Caroline for asking too many questions. Too imaginative, she’d written on my report card. Disorganized. Curiosity, it seemed—encouraged the year before by our kindergarten teacher, Miss Mellion, a smart Londoner who wore blue angora miniskirts and whose voice had a melody like one of Mary Poppins’s chimney sweeps—was now punished.

Sister Caroline was stout, with a pinched, doughy face, and if you stood close enough to her, there was an odd, shuttered smell. She was a visiting nun from another order and wore a different habit—starched, short, and striped—not the flowing black robes of Mother Brown or Mother Ranney. She also lacked their kindness. Her sharp eyes were always darting, never seeming to rest or take you in. She was the only nun I ever truly hated, and I wasn’t alone in this. What pleased her was order. What provoked her was expression. She was an expert in phonics, but her teaching was joyless, and her frequent reprimands, from which no one was immune, usually took the form of being banished to the stool in the Stupid Corner (while the rest of us had lessons) or coloring “baby papers”—simple outlines of flowers and puppies—with dirty crayons. Tougher girls, like Nancy or Christy, were able to laugh it off, but I wasn’t. And after I refused to open my milk carton during milk break—because I could never finish it all and what about all those starving children in Ethiopia—her dislike of me became acute.

That day, the hand bell had been rung, all the doors were shut, and I was alone in the long white hall. This was one of the worst censures, second only to being sent to Reverend Mother’s office, and it was the first time for me. I had no idea why I was there, and I wanted to hide. There was the cloakroom behind the elevator, the play deck on the roof above, or the dusty wings of the velvet-curtained stage in the assembly hall two floors down. Shame welled up in me, and I began to cry. I realized that the only way to get through the rest of the year with Sister Caroline was to dim myself, to silence whatever voice I had.

Blinded by tears, I turned down the hall. By the kindergarten rooms, thumbtacked neatly on bulletin boards, were rows of colored paper with cracked finger paint and names written in Miss Mellion’s black felt pen. With all my heart, I wanted to push the classroom door open, grab one of the little-girl smocks that hung on hooks in the cubbies, and bury myself forever in Miss Mellion’s soft, warm, British lap. And when I realized I couldn’t, I began to sob harder.

Then something strange began to happen. I couldn’t move, the floor seemed to swell beneath me, and a wave of everything I remembered from the year before came over me: Miss Mellion’s throaty laugh, singing a song during show-and-tell, the rounded inkwells in our yellow wooden desks, the red rug where we lay at nap time, the delicate chiming of Miss Mellion’s bracelets, the sun from the open window on Elizabeth’s gold hair. I was frightened at first, but then I gave over to the barrage of color and sound.

When it was over, I was no longer crying. I had lost track of time, and that felt like relief. Although I sensed that six was a bit young for this style of reminiscing, I also discovered that memories of pleasure—of what I longed for and what no longer was—had calmed me. They were as real as the long hall I stood in or the Gospel words on the banner nearby or Sister Caroline’s virulent disdain of me. I took the secret of that day, and later, on nights when I couldn’t sleep, I would choose a memory. Lying on my back with my eyes shut to the dark, I’d pick one, imagining it was a selection on a jukebox. I would wait until, like a shiny 45, it dropped and slowly began to spin.

It might be that the desire to turn back is passed on. I believe that. But it could also be that this place so redolent of the past had claimed me, marked me, like the smudge of Lenten ashes burned from the blessed palms of the year before.

Famous people’s children went to Sacred Heart, and in that way, it was like any private school in New York. The nuns were indifferent—they treated everyone the same—but names were whispered down, as in a game of telephone, during gym or in the lunch line. There was the daughter of Spike Jones, a big band leader of the forties and fifties (this impressed my father to no end; he had an eight-track tape of Glenn Miller, and he played it on all our car rides); the great-granddaughters of Stanford White; the nieces of William F. Buckley and Carroll O’Connor; and, for one infamous year at the height of Watergate, John and Martha Mitchell’s shy, red-haired daughter, Marty. Caroline Kennedy and her cousins Sidney and Victoria were older than me. I saw them in the halls, during fire drills, or at congé, a surprise feast held twice a year, when we played hide-and-seek en masse and ate cake and tricolor ice cream in paper cups with lids that peeled off with a pop. But at that age, the world consisted of the thirty-two girls in my grade—and a few of the mean ones in the grade ahead.

On a spring day in 1969, when I was where I shouldn’t have been, I saw her. No longer Mrs. Kennedy, she had married the previous October and was now Mrs. Onassis.

Arrivals and departures took place on Fifth Avenue through a small door that led to an industrial staircase. At the end of the day, the older girls headed off with colored passes for the downtown bus or the crosstown bus, but the lower school girls boarded private buses, double-parked and yellow, or were met by mothers and nannies gathered on the sidewalk for pickup.

The formal entrance was on Ninety-first Street through a recessed half-circular drive, once a carriageway, that led to two sets of dark double doors. The covered drive, where we sometimes lined up for fire drills and class pictures, was a well of coolness, a cavern of stone. At either end of the drive, flung wide in the day and locked by the nuns at night, were fifteen-foot arched dungeon doors. This was the grown-ups’ entrance. We were allowed to use it only at special times, like First Communion and the Christmas concert, when the front lobby was home to a massive tree and a terrifying oversize crèche.

I don’t remember whether, on that day, I went there because it was spring, or because it was off-limits, or because I simply wanted to stand by myself in the cool between the doors. Nor do I recall how, before that, I found myself, between lunch and gym, alone on the first-floor landing.

I stood on the landing (where I was allowed) looking at the lobby (where I was not), and instead of turning left up the steps by the courtyard, I lingered. Except for Miss Doran, the receptionist, the large hall was empty. No one on the heavy benches that looked like church pews. No one at the ancient creaky elevator with the brass grate (also off-limits). It was a window that wouldn’t last.

My waist rooted to the handrail, I inched down a step. Miss Doran turned in my direction. She was chinless, and her head ended in a topknot. I watched as it bobbed. She was on the phone, a private call I could tell, and with her thumb, she kept tapping on the bridge of her cat-eye glasses. She saw me and she didn’t. When she swiveled her chair away from me, I began to walk—the polished doors just feet away—not fast, not slow, but as though I belonged, as though I were an upper school girl instead of a lowly third grader.

I made it through the first set of doors into the tight alcove with the lantern above. My heart raced. Realizing that no one had fo

llowed me—no nun, no Miss Doran, no handyman—I pushed open the second set of doors. Triumphant, I stood alone on the top step, looking at the tight-budded trees on the street outside.

But there was someone there. A woman backlit by the sun had just stepped through the arch onto the cobblestone drive, her face obscured by shadow. Behind her, a photographer was taking pictures. He looked curious to me, like a monkey bending in all sorts of ways, but oh so careful not to drop his camera or cross the line that divided the sidewalk from school property. Even through the flashes, I recognized the long neck, the dark glasses, and her hair just like my mother’s when she went to a fancy party. Tall, like an empress from a storybook, she glided toward me, without interest in the man who continued to take pictures of her back. Her face was calm, as if by paying no attention, she could will him from being.

When she was close, I saw her face, that her lips were curved. She took one step up, placed a gloved hand on the heavy doors, and was gone.

Years later, when we met, I remembered who it was she had reminded me of that day. It was the painting of the Lady with the Lily, with the same inscrutable smile.

The uniform we wore was nothing like the ones at the other girls’ schools nearby. Not for us the blue pinstripe or the muted plaid. We wore a gray wool jumper, a boxy jacket to match, either a white shirt with a Peter Pan collar or a red turtleneck jersey, gray kneesocks with a flat braid up the side, and brown oxfords bought at Indian Walk the week before school started. The shoes were hateful—like the ones nurses wore, with pink lumps of rubber welling from the sides. The only consolation was that everyone had to wear them. My mother made me polish mine once a week with a Kiwi kit (also from Indian Walk), and as I sat on the white-tiled bathroom floor inevitably scuffed with brown, it seemed to me a supreme waste of time to shine something that was so ugly to begin with.

There were two things that made the uniform bearable. At the end of each year, Miss Mellion picked six girls to clean up the lower and middle school costume closet, a windowless box of a room in the Burden mansion. And each year, I was one of her chosen. A limited amount of folding took place. Mostly, it was an entire day without classes, spent thigh-deep in feathers, chiffon, dust, and torn velvet.

The other thing was the ribbons, wide, grosgrain sashes in pink and red that Reverend Mother would slip over your left shoulder and fasten with a pin at your waist. They were awarded sparingly for overall excellence. I got only two in nine years. But it didn’t matter—they stood out in the sea of gray, a feast for the eye.

Every Monday morning in lower school, we had assembly, which the nuns called prîmes. We’d file down the stone steps from the fourth to the second floor, always by height, always silent, always to the left. We were girls in straight lines with wild hidden hearts—like Madeline. If the nun’s back was turned, one of us would make a break for the stone banister which was perfect for sliding and swept into a curling flourish at the bottom.

The assembly hall had been Otto Kahn’s music room, and there was a huge chandelier in the center and a shallow, curtained stage at the back. The teachers sat on upholstered chairs in front of the tall French windows overlooking the courtyard. They faced us and we faced each other. There were four rows of folding chairs on each side of the wide aisle, with the first grade in the front and the fourth grade at the back. Giggling and bored, we filed in and peeled off—half the class to one side of the aisle and half to the other. Reverend Mother came last. She was tiny, not even five feet, and we all stood when she entered the room.

As the teachers began to arrive, a shoe box was passed filled with balled pairs of white gloves, each with name tags sewn on by our mothers. Most of the gloves were thick brushed cotton, like mine, but some were trimmed with gold—a chain or a bow—and others were almost transparent, silky like a skating skirt or how it felt inside the top drawer of my mother’s bureau. The gloves were always tight, as though the shoe box were magic and the stiff cotton shrank from week to week. Even when I used my teeth to nudge them up, they barely made it to my wrist.

At the end of assembly, we filed up two by two to be received by Reverend Mother. The procession was elaborate and choreographed, and the nuns rehearsed us endlessly—the spacing, when to turn, how deep to curtsy. Ball heel, ball heel. Like water ballet or a bride’s walk. And when we finally got close enough, her eyes, magnified by the thick glasses she wore, were a filmy cornflower blue, and you could see the down on her cheek. She always smiled, but if she said something, you would answer, Yes, Reverend Mother. Thank you, Reverend Mother.

Prizes were given: medals, calligraphed cards, the pink and red sashes, and smaller ribbons in green and blue that we fixed to our jackets with tiny gold safety pins. I got ribbons for social studies, music, and drama, but what I wanted was the one for religion. For two months, I wanted it more than anything. I went to great lengths to furrow my brow in chapel and refrained from sliding down the banister, but the ribbon remained elusive. It always went to the same two girls—one with Coke-bottle glasses who told everyone she wanted to be a nun and the other who had the face of a Botticelli angel.

By the end of the year, I’d lost interest. I started reading books about Anne Boleyn, Sarah Bernhardt, and Lola Montez. I wanted to be an adventuress, an actress, or an archaeologist. But when Masterpiece Theatre began on PBS, I knew. I was transfixed by Dorothy Tutin in The Six Wives of Henry VIII and Glenda Jackson in Elizabeth R, and each morning during summer vacation, I would practice the two things that seemed essential to my future: how to raise one eyebrow and how to cry on cue.

There were games we played then. Hopscotch with colored chalk on the sidewalk and jacks on the slippery floor of my building’s lobby. In second grade, there was Dark Shadows and Lost in Space, and we’d fight over who was Angelique and Mrs. Robinson. Elizabeth Cascella and I had queen costumes from FAO Schwarz. With the phonograph blaring, we would dance around the floral couches in her mother’s living room and act out all of The Sound of Music. We adored Captain von Trapp—his profile and his uniform; we loved Liesl and her dress; but we wanted to be Maria in the opening credits, and we spun ourselves dizzy until the white ceiling of the room became an alpine sky.

And there were board games: Who Will I Be?, Trouble, and Mystery Date.

When I was ten, we had a new game, Paper Fortune. You rolled the dice, and that was your number. Then you made a list: five boys, five cars, five numbers, five cities, five resorts, five careers, and another five careers. On a piece of paper, you wrote each list on a separate line. Then, using your number, you began to count the words, crossing off the one you landed on. In the end, there was just one word in each row. You circled them with Magic Marker, and there it was: Your life. Who you married, what you drove, how many kids, where you lived, where you vacationed, what you did, and what he did.

The problem was boys. We didn’t know any, or at least I didn’t. For vacations, you could put down Monte Carlo or Colorado or the North Pole, places you’d never been. But the names of the boys had to be real, and though we didn’t have to know them, they had to be our age, not Davy Jones or David Cassidy or any of the Beatles. Invariably, I’d put down Billy, who lived next door in the summer. (We’d kissed in the barn, and when we were little we’d played dress up at my house, until his mother called my mother and said that he couldn’t.) A boy named Dwight I’d loved in nursery school. My friend Janie’s cousins, who visited every summer from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and taught me how to bunt in softball and cheat at cards. And someone’s older brother. Sometimes, though, I’d put down the boy from the barbershop.

From the time I could walk until I was eight, I got my hair cut at Paul Molé, an old-fashioned barbershop on Seventy-fourth Street and Lexington. It’s still there, on the second floor, but in a larger space a few doors down from the original. The photographs are still on the wall (some different from the ones I remember), and there’s the same wooden Indian on the landing, and skinny black combs in blue water.

As I fo

llowed my mother’s legs up the narrow wooden stairs, I would always stop by the pictures. They were black-framed and autographed, of newscasters and actors, and one down low of a boy my age with his hair cut long like my brothers’. Like every boy’s in New York.

In the photograph, the boy is skinny, all energy. Something has his attention and he is caught mid-turn, eyes away from the camera, with somewhere to go. He may have just finished smiling or he is just about to. But there is something in him I recognize and I want to reach up and touch the picture.

He’s the boy whose sister goes to my school, the boy whose mother is beautiful, and whose father was president before I can remember. But it’s not that.

I stand and wait, wait for him to turn back. I wait—until my mother calls me. And each time we climb the steps, he’s there.

Soon I’ll forget about the game, forget about the folded paper and the Magic Markers. And the boy with the hair in his eyes whom one day I will find again. But years later, on a balmy night in Los Angeles in the late 1980s, when John and I are at a party in the Hollywood Hills, a girl I’d gone to Sacred Heart with walked in. We hadn’t seen each other since we were fourteen. She was a model now, glamorous and high-strung, with an undiscovered David Duchovny like a jewel on her bare arm. He and John had been in the same class at Collegiate, and there, in a city so different from the one we’d grown up in, under a sky wider than the one we’d known, we caught up. When they leave to get the drinks, she takes my arm and pulls me close. Did I remember the nuns? she asks. How in first grade we pushed Sister Caroline down the staircase and in eighth grade we stole the wine from the sacristy? And what about the game? She leans in, her breath warm, and with something akin to shared triumph, whispers, “The game—you got what you wanted!”

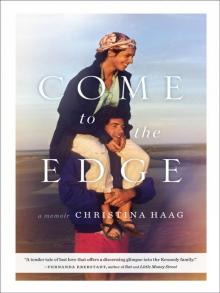

Come to the Edge

Come to the Edge