- Home

- Christina Haag

Come to the Edge

Come to the Edge Read online

Come to the Edge is a work of nonfiction. Some names and identifying details have been changed.

Copyright © 2011 by Christina Haag

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Spiegel & Grau,

an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group,

a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

SPIEGEL & GRAU and Design is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

ALFRED MUSIC PUBLISHING CO., INC.: Excerpt from “Love Is Here to Stay,” music and lyrics by George Gershwin and Ira Gershwin, copyright © 1938 (renewed) by George Gershwin Music and Ira Gershwin Music. All rights administered by WB Music Corp. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission.

DGA LTD: “Come to the Edge” by Christopher Logue, copyright © 1996 by Christopher Logue. Reprinted by permission of DGA, Ltd.

VINTAGE BOOKS, A DIVISION OF RANDOM HOUSE, INC.: Five-line poem from The Ink Dark Moon: Love Poems by Ono No Komachi and Izumi Shikibu, Women of the Ancient Court of Japan by Ono no Komachi and Izumi Shikibu, translated by Jane Hirshfield and Mariko Aratani, translation copyright © 1990 by Jane Hirshfield.

Reprinted by permission of Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc.

All photographs courtesy of the family of Christina Haag, except this page (Robin Saex Garbose) and this page and this page (© L.J.W./Contact Press Images).

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Haag, Christina

Come to the edge: a memoir / Christina Haag.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-679-60490-7

1. Haag, Christina 2. Television actors and actresses—United States—Biography. 3. Motion picture actors and actresses—United States—Biography. 4. Kennedy, John F. (John Fitzgerald), 1960–1999. 5. Kennedy family. I. Title.

PN2287.H14A3 2011 792.02′8092—dc22 2010045787

www.spiegelandgrau.com

Jacket design: Evan Gaffney

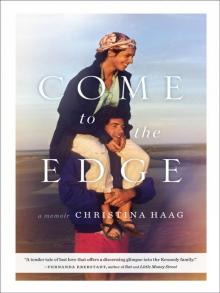

Jacket photograph: © L.J.W./Contact Press Images

v3.1

For my mother

Come to the edge.

We might fall.

Come to the edge.

It’s too high!

COME TO THE EDGE!

And they came,

and he pushed,

and they flew.

—CHRISTOPHER LOGUE

Amor vinciat

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

August 1985

Beginning

Waiting

Falling

Holding

Ending

After

February 1986

Acknowledgments

About the Author

August 1985

Seeing a place for the first time at night gives it a kind of mystery that never leaves.

John’s mother’s house in rural New Jersey was on a private stretch of road between Peapack and Bernardsville in an area known as Pleasant Valley. Bernardsville, a charming town an hour west of New York City, claims Meryl Streep as its hometown girl, and buildings from the turn of the century have been converted into video stores and pizza parlors. Peapack is smaller, quieter, with an antiques store and two churches. Close by are Ravine Lake and the Essex Hunt. The Hunt was founded in 1870 in Montclair but soon relocated nearby, and Mrs. Onassis rode with them for years. And in the surrounding fields of Somerset County, John had gone on his first fox hunt.

On the left side of the road as you approached the house, there was a meadow and a ridge with a dark line of trees at the top. On the right—country estates, deeper woods, and a small river, a branch of the Raritan. The house was nestled on a hill. What I remember is the peace and comfort of being there. It was a place to rest and recharge. Mrs. Onassis had a great talent for making you feel welcome, for creating an atmosphere of elegance and ease in all of her homes, although each had its own special character.

The cottage in Virginia, which she used during foxhunting season, was simple, with pressed linen sheets that smelled like rain, a sloping roof, and a large sunlit bathroom with a sisal carpet and a comfortable chair to read in. When John and I lived in Washington during the summer of 1987—he was interning at the Justice Department, and I was performing at the Shakespeare Theatre—we spent weekends alone there. It was a particular pleasure to sink into that deep tub on an afternoon, the rain beating on the roof, and listen as he read to me from the chair, a book of poems or Joseph Campbell or whatever novel he was reading.

The house in New Jersey had five bedrooms and an airy living room with yellow walls and French doors that opened onto a pool and a stone patio. It wasn’t grand or ostentatious; it was timeless and the colors subtle. You hadn’t realized that you wanted to put your feet up, but there was a stool waiting. You hadn’t realized that you wanted to read, but there was a light nearby and just the right book. Comfort and desire were anticipated, and you felt cared for.

But I didn’t know any of this on that summer night in 1985—I’d never been to either home. Tonight would be the first time I would stay at the house on Pleasant Valley Road.

Rehearsals had ended earlier that evening at the Irish Arts Center, a small theater in Manhattan’s West Fifties. It was a Thursday, and the play that John and I were in rehearsals for was opening that Sunday. Winners is set on a hill, and our director, Robin Saex, had always talked about running our scenes outside. She had been toying with spots in Central Park and Riverside when John volunteered a slope near his mother’s house in Peapack. It was steep, he told us—so steep we could roll down it! We would rehearse there on Friday, which would give the crew the entire day to finish the set and hang the lights in time for our first technical rehearsal on Friday night.

The three of us set off in his silver-gray Honda. When we arrived close to midnight, we found that supper had been laid out by the Portuguese couple who were caretakers of the house. They were asleep, but a very excited spaniel was there to greet us instead. Shannon was a pudgy black and white dog—a descendant of the original Shannon, a gift from President de Valera of Ireland to President Kennedy after his trip there in 1963. John scolded him affectionately for being fat and lazy and told him that the bloodlines had deteriorated, but the spaniel was thrilled by the attention.

On a quick spin through the house, he showed us his old room. It was a boy’s room—red, white, and blue, with low ceilings, some toy soldiers still on the bureau, and in the bookshelf Curious George and Where the Wild Things Are. Robin dropped her bags near the bed, and we went downstairs and ate cold shepherd’s pie and profiteroles, a meal I would come to know later as one of his favorites.

After supper, Robin yawned and said, “Guys, I’m turning in. We have a lot of work to do tomorrow.” I was tired as well, but too excited to sleep, and when John asked if I wanted to go see the horses in the neighbors’ barn, I said yes. He put some carrots and sugar cubes in his pocket, and we headed down the driveway and across the road to the McDonnells’.

Murray McDonnell and his wife, Peggy, were old friends of John’s mother. She boarded her horses with them, and their children had grown up together. The McDonnells’ hound, who spent most days visiting Shannon, began to follow us home, and Shannon, who never strayed far from his kitchen, trailed behind. John teased both dogs, saying they were gay lovers. He leaned over and shook a finger at Shannon, admonishing him again for being fat. “Don’t be too sweet, Shanney, don’t be too sweet. Or I will bite you. I’ll bite you.” Shannon thumped his stub of a tail and waddled back up the drive.

<

br /> It was one A.M., and I was getting the moonlight tour. When I asked if we’d wake the McDonnells, John shrugged and told me not to worry. He showed me an old childhood clubhouse, and we ducked through the small wooden door. He showed me the roosters and the barn cats and the caged rabbits. And when an especially eager bunny nipped my fingers through the chicken wire, he said that Elise, his mother’s housekeeper, ate them for treats. I whimpered—the desired response, I now think.

We moved into the cool of the barn and met Murray McDonnell’s gelding and John’s mother’s mount, Toby. Like us, the horses could not sleep—or had been awakened by a whiff of carrot. I was not a horsewoman by any stretch of the imagination, but I’d ridden summers until I was fourteen, and I knew how to feed a horse. Still, it felt like the first time, and I let him show me. I had begun to value when he taught me things—his patience, the joy he took, how he never gave up.

“See, you keep your hand flat and your fingers back.”

I stood close to him by the stall and he reached into his pocket.

“Let him take it, he won’t bite. Like this …” Toby sniffed, lowered his velvet head, then looked up expecting more.

“You try.” In the darkness, John had stepped behind me. “Go on, keep your fingers back.”

“I’ll just feed him a carrot.” The carrot, for some reason, seemed safe.

“Here,” he said, opening my hand and placing a sugar cube there. “Don’t be scared.” And with the back of my hand resting in his palm, the horse kissed mine and the sugar was gone.

Our hands broke. But his touch stayed with me as we fed the horses the rest of our stash. It was with me when we left the barn and walked out into the ring. And when I climbed onto the split rail fence, John hopped up beside me.

The moon was full, and we were quiet, watching the sky.

“It’s a blue moon tonight,” I said. “I heard it on the radio.”

“Oh yeah?” He crooned, “Without a dream in my heart, without a love of—”

“What is a blue moon?” I wondered aloud.

“It’s when there are two full moons in one month. Not as rare as an eclipse, but definitely rare.” Because of his time in Outward Bound and a NOLS stint in Kenya, along with his innate curiosity, he knew so much about the natural world that I didn’t.

“So it’s got nothing to do with being blue?”

He shook his head, smiling.

“But it seems special, like a stronger moon.”

“Maybe it is,” he said, looking into my eyes.

“Look.” I pointed. “It is brighter. Everything is silver—the leaves, the barn, the stones, the horses, the road, everything.” I shifted my weight on the fence. Everything.

Again we were quiet—the shyness that came from knowing each other well in one way, as we had for ten years, and then the knowledge deepening. We had been friends in high school, housemates in college, but now—walking home together these past few weeks, practicing the kiss in rehearsals, falling in love through the imaginary circumstances of the theater (a professional hazard for actors: Is it real? Or is it the play?)—attraction had become undeniable. We sat for a while under the stars and felt no need to speak. But then he did.

“Can I do this for real?”

He didn’t wait for an answer; he leaned in. Only our lips touched. It was gentle, hands-free, exquisite. I opened my eyes for a second, not believing that what I’d dreamed of was happening, and saw, by the lines at his eyes, that he was smiling. I held on to the fence, woozy. A world had opened.

“I’ve been waiting to do that for a long time,” he said, looking not at me, but at the sky. He was still smiling, and I remember thinking then that he looked proud. For the past week and a half, we had kissed in rehearsals, but in my mind, we were the characters, Mag and Joe, teenagers from Ireland about to be married because she was pregnant. At least I had tried to believe that. But this kiss was different. This kiss was ours.

“I guess that wasn’t supposed to happen,” he said finally, tucking one of his ankles behind the fence rail.

No. It’s right. Again. Don’t stop, I thought. Then my mind went to the actor I’d been with for almost three years, who was kind and good and could make me laugh, even in a rough patch, and to John’s girlfriend from Brown, whom I liked and admired. Reality. People would be hurt. Or did he mean it wasn’t supposed to happen because we were friends and should remain so? It occurred to me only later that he was testing the waters.

“Do you want to talk about it?” I asked.

He didn’t answer. Instead, he took my hand and said he wanted to show me something. I followed him into the woods, twigs snapping under our feet. The sky had grown brighter, and light danced through the thicket of elms onto the rocks and the river. Sound rushed, loud and exhilarating. In my dreams, I’d promised myself one kiss—just one—and now I’d had that.

John stepped into the shallow river and sloshed around in his sneakers. I took off my sandals and jumped from rock to rock as he steadied me, and when I finally gave in and stepped down into the cold water alongside him, it woke me. I felt alive. I’d been quiet in the barn, but now I could not stop talking. Nerves, excitement, happiness—I’m not sure which was stronger. We talked about our childhoods. I told him how I hid in books, loved the ocean, didn’t like sports but adored ballet. “You sound like my mother,” he said, somewhat under his breath. “But I seem to recall a table or two you danced on in high school.”

I told him stories about my younger brothers and about the nuns at Sacred Heart, where I had gone to grade school and where his sister had also gone. He remembered the building on Fifth Avenue, he said, and its covered driveway. He’d gone to St. David’s, two blocks down, and in the afternoons had walked with his mother or his nanny to pick his sister up. He told me about playing in this river and making forts, about being bloodied in a fox hunt nearby—an initiation rite in which boys are dabbed with the blood of the kill—and about how, when he was a toddler and the first Shannon was a puppy, and a mess was made or sweets were taken from the table, his mother didn’t know whether to scold him or the dog. He laughed when he told that story. But his mood darkened when he told of another Shannon, the one he loved best, the one who was irascible. He had been away for part of the summer, and on his return, he found that his mother had given the dog away. “I didn’t even get to say goodbye,” he said sadly.

It’s strange how one kiss can make you remember what is long past but what has made you who you are.

Upstairs, before we went to bed, he shared his toothpaste with me. Looking at his face in the mirror beside mine, I wondered if he always brushed his teeth so long. He didn’t seem the type. I knew I wasn’t. I just didn’t want the night to end.

“Good night,” he said finally, grinning in the hallway between the bedrooms.

“Good night,” I said, grinning back, but neither of us moved.

We kissed again. This time, he pulled me to him, and our bodies met like they’d always known each other. I’d never been kissed so slowly. He stroked my back and buried his face in my hair and kissed my neck. He was wearing a soft cotton shirt he had gotten in Kathmandu the year before. It was white, and on the back there was a large evil eye embroidered in turquoise and black. I felt the loose threads and his muscles beneath them. I felt his hand at the small of my back. Then I smelled something. Mint. In our passion, his toothbrush had become entangled in my hair. We looked at each other, realized, and began to laugh. I had toothpaste in my hair and I was happy. I was drunk with it. Then I pulled back.

“I hate to say good night—”

“Would you like to spend it with me?” he said softly.

Was this something he did easily? What would it mean? Would it be one night? And the play, would it change the play? Out of the corner of my eye, I saw a large and what looked to be quite opulent bed in the guest room, where his bags and the dutiful Shannon waited. At that moment, there was nothing I wanted more than to be with him. But other though

ts flashed through my mind, and I behaved not as I desired, not as I’d fantasized, but like the coy Catholic girl I was. The eroticism of waiting.

I stepped up on the landing that brought me closer to his height and whispered, “I would, but it’s … complicated.”

He smiled. “Well, if it ever gets uncomplicated …”

I was confused. “Isn’t it for you?”

“Oh, I’ve had a lot of time to think.” He dropped his head to one side, as if that way he could see me better. “I’ve walked you home so many times and trudged away alone.”

What did he mean? Before I could speak, he brushed the hair from my face and pulled me close.

“But one more kiss.”

This time it was harder to resist.

I stayed alone in Caroline’s room that night—a girlhood room with twin beds in white eyelet, and trophies and colored ribbons from horse shows. The setting was virginal, but my thoughts were not. I stared at the ribbons late into the night, unable to sleep. It wasn’t just the play opening, or the moonlight flooding through the window, or the smallness of the bed. It was the knowledge that our rooms adjoined through the hall door and he was sleeping so near. It was the knowledge that a kiss we had shared near a field by some horses might change my life forever.

Beginning

Within you, your years are growing.

—PABLO NERUDA

In the cool of a June evening long ago, a man holds a child in his arms. Across the field, light is falling behind a bank of trees and resting on a water tower, a dome of red and white checks. She’s in a cotton nightgown and her legs dangle. He is wearing tennis whites, but they’re rumpled. They always are. No socks, his shirt untucked. Behind them, a shingled summerhouse rambles down to a dock and a muddy bay. Near the kitchen door, a painted trellis is heavy with the heads of pale roses bowing.

Every night they do this. He sings her made-up songs and tells her stories. Some are silly, and she laughs. Daddy, she says. Some are of women in long dresses. Some of a princess with her name and a knight who slays dragons. But on summer nights, as he does on this one, he points to the tower and tells her it is hers. Her very own. He tells her, and she believes him. His eyes, sharp like the blue of a bird’s wing, gaze into hers. She lays her head against him, hair damp from the bath, and breathes the salty warmth of his skin. She wraps her legs at his waist and curls into him as the story ends and the light dies.

Come to the Edge

Come to the Edge