- Home

- Christina Haag

Come to the Edge Page 11

Come to the Edge Read online

Page 11

“Still, it’s something.” He got up and moved around the desk, his hands clasped tight behind his back, his head proceeding slightly in front of his body. “I believe it’s love,” he concluded with some distaste, as if I were an awkward bit of staging to be solved. “You’re addicted. I believe you’re in love with love!”

I burst into tears and began to apologize.

Michael handed me a handkerchief from his pocket. He didn’t require details, and for that I was grateful. It was about the work. He patted me lightly on the back and told me to take care of things. “We have great hopes for you,” he said before I reached the door. I turned and saw that his face had softened. There was a rim of red wetness around his jeweled eyes, a sort of kindness.

At the end of November, I got an invitation to John’s annual birthday bash, this time at a club in Midtown. It was a curt, breezy note, something about losing my address. You can, of course, bring a date, he wrote. I went alone, and when I saw him through the crowd, laughing easily, surrounded by friends, I knew he had moved on. And I was sure of something else—I had made a huge mistake that night in the park. It had taken me that long to know. As I left the party, there were flurries in the night air, but they melted before they hit the pavement. I wondered if everything that had happened that summer had meant nothing, if it had just been a mirage of the play, a trick of the theater.

A smaller voice said, Wait.

Then in December, I ran into him at a Christmas party in the East Twenties. He’d come with his girlfriend, and I was meeting Brad later, but at some point, we found ourselves in a corner of the kitchen, and the steely awkwardness that had been there all fall had vanished. We flirted. The light in the room was bright and we weren’t alone, but it felt as if we were. And before I left, he asked if I would meet him the next day. He needed help picking out a gift for his sister.

“Favorite memory?” I repeated the question.

After lunch, we wandered all afternoon near the planetarium, past the stores on Columbus and then down to Lincoln Center. Now we were on Broadway again—walking each other back and forth between Seventy-ninth Street, where my bike was locked, and Eighty-sixth, where his apartment was. It was after four and we kept putting off saying goodbye. As we walked, our breath came out in short white puffs.

My hands were cold; I’d forgotten gloves and he offered his. Stitched brown leather and fuzzy on the inside.

“Favorite now … or of all time?” I put the gloves on. Even with space at the fingers, they were warm. I kept one for myself and handed him back the other.

“Childhood. The best one.”

I closed my eyes, and I was there. Running up the steps in a cherry velvet dress during intermission at The Nutcracker to touch the beaded metal curtain that hung by the tall windows across from the bar. I’d turned my back and pretend to look out on the giant courtyard. Careful at first, I’d make the beads sway—the weight on my fingers a pleasure—but when I saw, balconies below, that the curtain rippled into a full-on spin, I’d get bolder, my touch now a jangle, until a guard or my mother would stop me. It was as much a part of the tradition as the Sugar Plum Fairy or the Christmas tree that grew.

Sunday dinners with my kindergarten best friend at a Chinese restaurant on Third Avenue. Wide round tables at half-moon booths, a fountain of magic rainbow-colored water at the entrance, and uniformed waiters who’d load up our Shirley Temples with maraschinos. We’d gnaw the stems and line them at our plates like twigs. Halfway through dinner and bored of our parents, we’d slide off the shiny vinyl banquettes to whisper secrets under the table. The starched tablecloth—a cave entrance—and our mothers’ legs poised, even in the darkness.

And skating at Rockefeller Center—always cold, always shadowy—but the music and hot chocolate were better than at Wollman Rink. Plus they had rental skates that didn’t make your ankles buckle.

“Well, Madam?” he persisted. Under our boots as we walked, the crunch of salt and ice.

“The World’s Fair,” I answered. “I’m almost five, and my mother’s in a beige suit and heels, very pregnant. I remember going with my father up to the highest deck of the observation tower—the one that’s still there and looks like a spaceship. We went in one of the small exposed elevators that rode up an outside track, but my mother stayed below. I held my father’s hand, and the whole time I could see her, but she got smaller and smaller. And when we reached the top, I could see the tip of the city over the trees, and my father leaned down and said he was proud of me. Then we went on It’s a Small World After All, and I got to sit between them in those little boats.”

“It’s a Small World … I remember that!” To prove it, he hummed a bar. “We went with my cousins Anthony and Tina. Maybe we were there at the same time.”

“Maybe …”

“Remember the goats?”

“Oh my God, I do!”

“I liked those goats,” he said, as if he still missed them. He began to shake his head softly, a smile beginning on his lips.

“I was wrong about you. I was sure you’d say Serendipity.” He was referring to the fancy ice-cream parlor near Bloomingdale’s, with the faux Tiffany lamps and the spiral staircase, where Upper East Siders had birthdays in grade school. “Girls always like Serendipity. I thought that would be your favorite.”

I smiled. I liked it fine, I told him, but there were other things I liked better.

His face had gotten wistful in the sudden dimming light. After a moment, he turned to me. “I have to tell you … I didn’t think you were going to show today.”

His eyes caught mine. I’d thought the same thing about him.

“But I’m glad you did. I’ve missed this.”

Those were the words I needed, the ones I’d waited to hear; and we walked faster, whether from cold or happiness, I did not know.

West by the river, there was a last gasp of sunset. We’d arrived at the corner of Eighty-sixth and Broadway for the third time, and the streetlights came on. When he turned, like an admission, to walk me back once more, we laughed.

“What about you—what’s your favorite?” I asked.

“Beatles. Shea Stadium.” For him, there was no pause.

“You were there?” I gasped. “How old were you?”

“Five,” he said, satisfied. “And hansom cabs.” Except, he told me, every time there was a major change in his life—a new school, his mother marrying Onassis—she’d take him for a carriage ride around the park to break it to him.

“Ah, you couldn’t escape.”

“Too true,” he chuckled. “Too true, I couldn’t.”

We stopped in front of a dress shop that had always been there. In the window, there were sale signs written out in Magic Marker and old-fashioned mannequins covered in polyester jersey.

“I remember this place, it was here in high school,” I said.

“Wanna know something?” He leaned in, and where my scarf had loosened, I felt his breath. “I bought my mother a dress here once. A present in fifth or sixth grade. Two dresses, actually. For $19.99.”

I was charmed and asked the obvious. Did she wear them?

“That night she did.” He closed his eyes, remembering. “But only in the house. She was very convincing. She said she loved them. She said they had style.”

We’d reached Seventy-ninth Street for the last time, and there, on a crowded corner at twilight, between a Baptist church decked in Christmas wreaths and a news kiosk, he kissed me. Before we parted, I handed him back the glove, and he took both my hands in his and pressed them to his lips. And the snow that had been promising all afternoon to fall had finally and quietly begun.

I left for Mexico the next day, a family vacation, but stayed on an extra week to travel on my own. I slept in a hammock in Yelapa, downed shots of tequila before parasailing, and spent New Year’s Eve on a cliff top with strangers toasting the sky. I thought the time away would make me sure of what I already knew. When I returned two weeks later, there was

a letter waiting. It was short and to the point. As he filled out his law school applications, he couldn’t stop thinking of me. “I’m imagining you all alone in the hot Mexican sun,” he wrote. Unlike the missives from India two years before, with their crossed-out words and serpentine scrawl, he had printed each letter squarely, perfectly, without confusion.

“PS,” he added at the bottom. “I want to see Your Tan.”

I waited a few days, then called him, and this time I didn’t look back.

We stood on the pavement between Eighth and Ninth avenues waiting for cabs, a huddle of friends from college. We’d been dancing that night at a new Cajun restaurant, once an old post office annex. John had a new job at the 42nd Street Development Corporation. The office was next door in the McGraw-Hill Building, and the restaurant was his find. He would rent it out, or his friends would, for birthday parties, celebrations, and, as people we knew began to get married, the odd bachelor party. With the tables pushed back, it made for a great dance floor, and at night, with Talking Heads or Funkadelic blaring, the large picture windows that faced the vacant lot and the welfare hotel across the street made it a snow globe of light on what, in the mid-1980s, was a desolate stretch west of the Port Authority. When I arrived alone, the party was in full swing.

I had been in a play that night. Each spring at Juilliard, the members of the graduating class perform for two weeks in repertory, a nod to the European roots of the training. It was thrilling to shift gears and worlds like that; it was why I wanted to be an actor. The slate that spring was a Jacobean tragedy, O’Casey, Ibsen, and Sam Shepard. Tonight—the tragedy. I was Annabella, murdered for her incestuous love of her brother Giovanni. Believing their passion is pure, they forgo morality and society’s judgment, and when they cross the line to carnal pleasure, it seals their fate. Romeo and Juliet with a twist.

When I came offstage, I removed the heavy makeup and the wig of human hair the color of mine but longer, thicker. I let the brocade gown drop to the floor and stand by itself in a poof. I untied the hoop skirt and unlaced the stays of the boned corset. I pulled off the wig cap and the bobby pins that held the pin curls to my head and made the wig lie flat. I shook out my hair, lined my eyes with black pencil, and slowly inched fishnets up my legs. A tear; I pulled higher. Then I put on the new dress I’d bought at a thrift shop behind the planetarium days before. I slipped the black sheath of silk crêpe over my head—slim straps on the shoulders and a bias-cut; it fell to mid-calf and flared slightly there.

With six dollars and a token or two in my pocket, I headed to Columbus Circle to catch the A train. I slung my Danish schoolbag across my back; it was purple and stuffed with dance shoes, leotards, scripts, scarves, the Post, a red paperback of Yeats’s poems, and my journal. When I reached the subway steps, I changed my mind and hailed a cab. The bag was heavy, and I was eager to get to the party. Anxious, too. Chris Oberbeck, our roommate from Benefit Street, was getting married to his college sweetheart, and this shindig was in their honor. Although John and I had been seeing each other for almost three months, this was the first time we would be together as a couple with people we’d known for years.

Our courtship since mid-January had been hidden, sporadic, and intense. Separating from the long relationships we’d been in—John’s for five years and mine for three—had proved more difficult and painful than we had imagined. And there was the fact that we’d known each other for so long. I was afraid that if I took the leap, I might lose my friend. What was undefined held safety.

One February night, as I was walking to meet him, the wind bit the backs of my knees and my mind raced. This can’t work … How can he … What should I … But when I saw him at the street corner waiting, his chin tucked, his head dipped to one side, I only knew I was where I should be and this was right. There was nothing else.

Still, it was stop-and-start.

In late January, he’s going to a conference in Pennsylvania, and he asks me to meet him there afterward. “To take a weekend together,” he says. It’s not a concept I understand. I have boyfriends, and we just do things. But for some reason, I find the phrase so sexy. He describes the hotel where we’ll stay, a place he’s never been. “There’s a heart-shaped Jacuzzi in the room,” he says, reading the brochure. On January 28, the day the Challenger crashes, he leaves a short message on my answering service saying the trip is off. I don’t understand at first—it’s a tragedy, surely, but not one that affects him directly. When we speak, he explains. His presence is required at the memorial service at the Johnson Space Center in Houston with President Reagan and other dignitaries. It’s either him or Caroline, and his ticket is up, Jacuzzi or no.

…

We meet for lunch at Café Madeleine on West Forty-third Street, and he whispers, “I miss your ears. I miss your hair, your freckles, your laugh.”

I leave school one day, and tied to my bike I find red roses and a postcard of a French courtesan. On the back, unsigned: YOU RULE MY WORLD.

We’re at the Palladium. As we dance, he moves to shield me from a photographer I haven’t noticed. Unlike mine, his eyes are peeled for that sort of thing. In the picture, I am laughing. I think it’s a game. The caption reads, “Mystery Woman.”

Headed to Martha’s Vineyard in a small plane, we hit a winter storm. Buffeted by high winds, we’re rerouted to Hyannis. With no place to stay, we arrive unexpectedly at his grandmother Rose’s fourteen-room house. It’s late. On our way up the dark staircase, we run into his aunt Pat in a Lanz nightgown. She’s in her cups. Then his uncle appears. Neither knew the other was there. Upstairs, we find a bedroom that’s used only in summer. We push the twin beds together and lie under the thin coverlet, as the wind rages. In the morning, before we leave for the Vineyard, we walk on the breakwater as far as we can go. The waves slap the sides and he steadies me on the wet rocks.

On a warm day, he bikes from Manhattan to Park Slope with tiramisu from his favorite restaurant, Ecco, melting in his backpack. We eat it on my brownstone roof, homing pigeons cooing nearby, and watch the light fall over the faraway city.

…

A morning: He kisses my forehead and tells me to sleep in, tucking me into his king-size water bed. When I wake up, he’s gone.

After seeing Ronee Blakley at the Lone Star, he gives me the first of many driving lessons. In this, he is both brave and patient. I’m a born New Yorker, and driving is not in my skill set. With the Scotch from last call warm in our throats and Al Green in the tape deck, I sit on his lap, and we drive his Honda in circles around the Battery Park lot for what seems like hours. The stars are white and cold, and we laugh as he explains over and over how the engine works, what it does. And I learn somehow. I learn well.

But there are weeks I don’t see him. Things are not resolved with his girlfriend, and they’re not for me either. After one stretch in March when we haven’t spoken, John appears at a performance of Buried Child. I am Shelly and spend much of my time onstage in a patchwork bunny jacket peeling carrots. A friend who is there that night tells me that John wandered the halls alone at intermission humming to himself.

Afterward, we meet and cross Broadway to McGlades, a bar where the Juilliard actors and dancers congregate. It’s awkward at first, until after a beer or two, he suddenly reaches across the table. Half out of his seat, he takes my head in his hands and pulls me closer, the table wedged between us.

“I was going to leave right after the play. I keep trying to forget you, but I can’t. I can’t let go.” His words come so quickly. He looks worried.

“What?” I say.

“I’m obsessed with you. I can’t stop thinking about you.”

“What?”

“I’m obsessed. You make me an emotional person, and I’m not.”

“No, John …” I laugh, taking his hands from my ears. “I can’t hear you.” I hold them between mine over the table, and we smile knowing something has been laid bare.

“You’re funny,” I say.

; “Why?”

“You’re a funny boy. You can only say that covering my ears.”

He sighs, but he doesn’t look away. “I’m scared.”

“I’m scared, too,” I say, but we’re both smiling.

As if to assuage me, he kisses each knuckle, then turns my palm over.

“I can’t stop looking at your hands. There’s a poem … have you seen Hannah and Her Sisters?”

Yes, I tell him.

“When I saw it, I kept thinking of you. You look like the actress. Your hair. When Michael Caine’s in the bookstore and he gives her the book—”

“I remember. ‘Nobody, not even the rain—’ ”

“ ‘—has such small hands.’ ”

He leans back and his eyes close. I touch his cheek. “What are you thinking?” I ask, but he shakes his head.

“What is it?” I make him look at me.

“On the street—I keep thinking I see you. You make me emotional, and I’m not like that. I want to say your name all the time.”

The cab stopped on Forty-second Street, and I walked across to the restaurant. Through the glass, I could see faces I knew. Happy. Young. Some from high school, most from college. John’s roommate, Rob Littell, with his shirt askew, was sliding across the floor doing his ski move. Art majors boogied in groups, punctuating with jumps and hoots. Classicists shimmied solo. Girls who grew up in Manhattan took up space, looping around the sides of the room and executing serpentine finger drills worthy of Indonesian temple goddesses. Frat boys got down with Iranian beauties, making up with enthusiasm what they lacked in finesse. I dropped my bag by a pile of jackets near the door and found my friends, the roommates from Benefit Street. Chris was talking to Kissy, and Lynne stood close to her boyfriend, Billy.

“He’s here somewhere,” I heard Lynne say over the din. “He was just asking about you.”

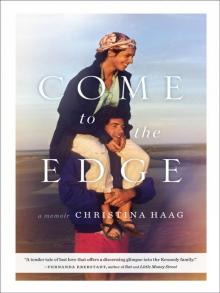

Come to the Edge

Come to the Edge